Battle of El Alamein

El Alamein 1942: British tanks move up to the battle to engage the German armour after the infantry had cleared gaps in the enemy minefield.

El Alamein 1942: British tanks move up to the battle to engage the German armour after the infantry had cleared gaps in the enemy minefield.The Battle of El Alamein (the second battle) was one of the most decisive victories in WWII. It was fought between two of the best commanders in World War II, Montgomery for the Allies and Rommel for the Axis, between 23 October – 4 November 1942. The Allies’ victory at El Alamein led to the surrender of the German forces in North Africa in 1943.

First Battle of El Alamein

Contents

The first Battle of El Alamein occurred between July 1-27, 1942. It was part of the Western Desert Campaign of World War 2 was fought between the British Eighth Army led by General Claude Auchinleck and the Axis forces consisting of German and Italian units of Panzerarmee Afrika (Panzer Army Africa) led by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. The battle would result in a tactical stalemate but a strategic Allied victory in that it halted the final advance by the Axis powers into El Alamein, Egypt. This battle would set the stage for the 2nd and more decisive Battle of El Alamein.

Battle of El Alamein Commanders

Allies

- Harold Alexander (UK)Bernard Montgomery (UK)

Axis Powers

- Erwin Rommel (Germany)

- Georg Stumme † (Germany)

- Ettore Bastico (Italy)

El Alamein Order of Battle

Allies

- 195,000 men

- 1,029 tanks

- 435 armored cars

- 730 – 750 aircraft (530 serviceable)

- 892 – 908 artillery pieces

- 1,451 Anti Tank guns

Axis Powers

- 116,000 men

- 547 tanks

- 192 armored cars

- 770 – 900 aircraft (480 serviceable)

- 552 artillery pieces

- 496 Anti Tank Guns – 1,063

Battle of El Alamein Casualties

Allies

- 13,560 casualties

- 332 – ~500 tanks

- 111 guns

- 97 aircraft

Axis Powers

- 30,542 casualties

- ~500 tanks

- 254 guns

- 84 aircraft

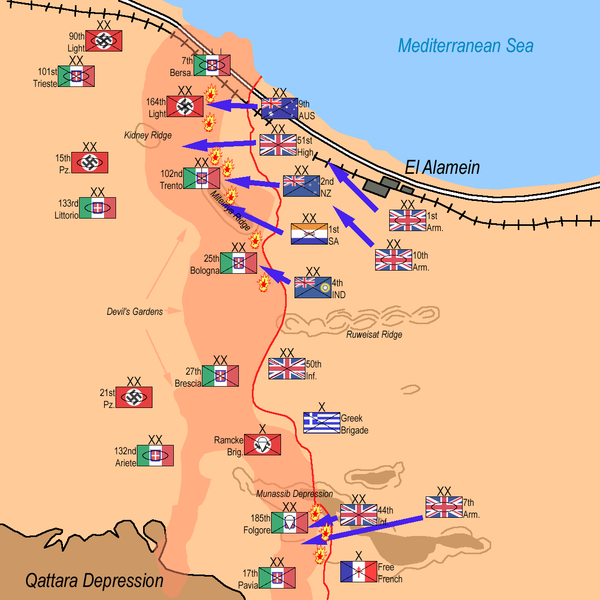

Battle of El Alamein Map (Attack)

Battle of El Alamein Map (Break Through)

Battle of El Alamein Video

Battle of El Alamein Summary

El Alamein is located 150 miles west of the city of Cairo. In 1942 the Allies had many troubles in Europe. Germany had launched its attack on Russia, codenamed – Operation Barbarossa, and succeeded in pushing the Russian troops back, the German U-boats were one of the biggest advantages the Axis had over the Allies in the Battle of the Atlantic, and it seemed like western Europe was entirely in Nazi Germany’s grip.

This was one of the main reasons why North Africa was so important for the Allies; if they had lost Africa, they would lose one of the last ways to get supplies; the only alternative would have been South Africa, and that was not only a much longer route but also much more dangerous because of the harsh weather conditions. Not to mention the psychological effect it would have had if they were to lose the Suez, control of the Suez would have also given the Germans almost unlimited access to the oil reserves of the Middle East.

El Alamein was, without exaggeration, the last stand for the Allies in North Africa. The town of El Alamein was also favorable for Rommel’s battle strategy, which consisted of attacking the enemy from the rear. Interestingly enough, Rommel was very well respected in the eyes of the Allies; the German commander had more respect in the ranks of the Allies than their commander at the time, Claude Auchinleck.

In August 1942, Winston desperately needed a victory and replaced Auchinleck with Bernard Montgomery, who was well-respected by Allied commanders. Rommel’s plan was a surgical attack in the south, which Montgomery guessed because that’s what Rommel had done in the past, but that wasn’t the only intelligence he had. He also got some help from people who worked at Bletchley Park; they managed to get some of Rommel’s battle plans and delivered them to Montgomery. Because of this info, ‘Monty,’ as his troops nicknamed him, not only knew what Rommel’s battle strategy would be but also what the routes of his supply lines were.

By August of 1942, Rommel was only getting one-third of the supplies he needed; Rommel also knew that even though he needed supplies, the Allies were getting everything they needed through the Suez, as the situation was only going to get worse, it was decided that they should attack as soon as possible, even if that meant that they wouldn’t be as well-equipped.

Montgomery knew that Rommel would attack soon as he was very short on fuel, so the campaign Rommel planned would be short. Montgomery was sleeping when Rommel attacked; when he was woken and told about the attack, he just said, “excellent, excellent,” and went back to sleep.

When the German forces arrived south of El Alamein, they would find themselves in the middle of a very nasty surprise; the Allies had placed an enormous amount of mines at that location, knowing where they would be attacked. The mines disabled many of the German Panzers and turned the rest of them into sitting ducks. This was already a hint of how the Battle of El Alamein would go. Rommel ordered the rest of his tanks to the north, where he had some help from mother nature. A sandstorm suddenly appeared and provided his tanks with much-needed cover, but as soon as the sandstorm was over, Allied bombers hit his forces, destroying the very place where the Panzers stood; at this point, Rommel didn’t have much choice but to retreat.

The Allied forces didn’t immediately go after them; they waited for more firepower, 300 Sherman tanks. At this point, the Germans had 110,000 men and 500 tanks compared men and 1000 tanks of the Allies. The Allies had to clear a 5-mile vast minefield created by the Germans nicknamed ‘Devil’s Garden’. The Allies wanted to earn a passage of 24 feet so that a line of tanks could pass through it. This plan ultimately failed, which would later lead to another battle that would be fought between Rommel’s men and Australian forces.

Battle of El Alamein Conclusions

The last part of the Battle of El Alamein was Operation Supercharge. British and New Zealand forces attacked the Germans, who were surprised but again saved by a sandstorm. Despite his excellent luck Rommel couldn’t win the battle; the Allies outnumbered his men and his tanks. By November 1942, the Battle of El Alamein was more or less over; Rommel knew that he was defeated and began his retreat despite orders from Hitler to fight to the last man resulting in a decisive Allied tactical and strategic victory.